NEWS CENTER – Not only Kurdish people had the opportunity to visit Chairman Abdullah Öcalan. As Rêber Apo pays special attention to the worldwide internationalism and in this context he founded the PKK from the beginning with internationalist hevals like Kemal Pir and Hakî Karer, he called the revolutionary organizations and internationalists to come to the free mountains of Kurdistan within the framework of the Workers Party of Kurdistan, the PKK party to deal with the PKK and its proposals for a worldwide internationalist movement.

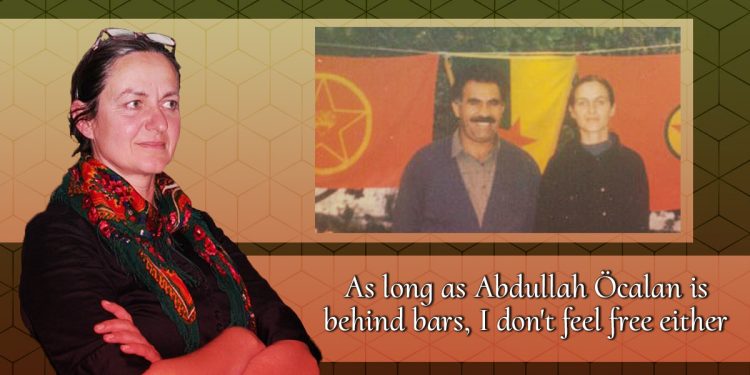

In this framework, the German internationalist also found her way to Kurdistan, to the chairman Abdullah Ocalan, who was currently living in Aleppo, and to the free mountains of Kurdistan where she spent two years with the guerrillas. Our news agency spoke with Anja about her experiences with Rêber Apo, which make it clear that Rêber Apo is not only the chairman of the freedom-loving peoples in Kurdistan, but his paradigm is destined for the whole world.

Can you introduce yourself briefly?

“My name is Anja. I have had a close connection to the Kurdish women’s movement since 1993. In 1995, I spent three months at the PKK party school in Damascus and was able to meet Abdullah Öcalan there. That same year, I went to the mountains as a guerrilla of the YAJK (Yekitiya Azadiya Jinên Kurdistanê) and stayed there until the end of 1997. When I returned, I was able to see the chairman again, albeit briefly.”

You met Chairman Abdullah Öcalan, had the opportunity to see him. How was that for you as an internationalist to see the chairman?

“At first, I have to admit, I had no real access to Abdullah Öcalan, coming from the German left, I was burdened with the usual prejudices. I could not really understand and appreciate his work and his contribution to the revolution in Kurdistan. He is not a person who was immediately sympathetic to a German leftist of the 1990s. The agitation in the German also left media obviously had an effect on me as well.

Over time, however, I understood better. He had public dialogues with friends in the academy, he took the time to talk to each person, to understand with what questions and personality he or she had come, whether there was an honest desire to be part of the revolution and to contribute to it. He has the ability to see the deepest inside of people, to see how they lie to themselves and delude themselves. He believes that they can change, that they can truly become people who change the world, that the world can be changed. Especially here in Europe, this belief the power of this confidence is weak, there is a lot of doubt and fatalism.

We were not the first Germans to be in the party school. He had already noticed with other comrades that they had come strongly influenced by individualism, without really being part of revolutionary organizations. Therefore, he already had an understanding of what problematics stood in the way of us wanting to participate. I only started to question my socialization in German society and the German left in Damascus. Before that, I had never really been organized and quickly realized that I also had no analysis of the world situation, the situation in Germany, in Europe, the women’s movement. Nor had I ever been part of a real collective. This is perhaps our biggest problem as a German left, that we are very strongly influenced by individualism and were not socialized in a community like many Kurds. I understood that the Kurdish women, although many of them didn’t have a classical school education at the time, were very much ahead of me in terms of political education, knew much more than I did, had a concept of their own situation and the way out of it.”

What was his approach to you, as an internationalist? How did he behave?

“In the 1990s, there was Abdullah Ocalan’s call for all revolutionaries and revolutionary organizations around the world to come to the Kurdish mountains and deal with the PKK’s proposals for a worldwide internationalist movement. Accordingly, it was very important to the party and Ocalan that we understand what the movement is all about. We had the opportunity to participate in all the discussions, to talk to all the comrades, no curtain was closed to us, everything was translated for us. This was very costly for the friends at that time. Even though we were such a diffuse little group, Abdullah Ocalan made sure that we learned as much as we could about the movement. So within three months we were able to learn and understand a lot. That helped me a lot later in the mountains and was very valuable.

He even suggested that I stay at the academy for one more training session. Unfortunately, I did not accept this offer, which I later regretted very much. In the mountains in a very hot war, there were few opportunities for political education. He understood me better than I understood myself. He saw my shortcomings clearly. That’s one of his qualities, that he’s a very good judge of character and can basically look into the heart and soul of the people he meets.”

Did you talk to each other? Can you remember what he said to you?

“When I was there in 1995, he obviously understood quickly that I didn’t have answers to the questions that needed to be asked, even to advance a revolutionary movement in Germany. We initially had the task of writing a brochure about the Kurdish movement, which we did.

In 1997, after I had been in the mountains for two years, he wanted to know above all from me whether I wanted to become a free woman, not in the sense of how women’s liberation is understood here in the West, but in the sense of a revolutionary woman who advances society, women as a whole. He suggested that I write about the movement, which I have been trying to do ever since. At that time he also offered me to stay longer in Syria. That would have been very good for me to learn about Kurdish society even beyond the military forces, but I didn’t want to listen and approached my future planning individualistically and naively.”

What impressed you most about Rêber Apo?

“I was able to get to know him as a person who devotes all his time and life to the revolution. A person who thinks very big. In 1993, he had proposed to the women to create their own army. I got to know the Kurdish society a little bit and at that time this was an outrageous proposal, many women did not feel able to take on such a task and many men believed women did not belong in the army at all. Öcalan was thinking far ahead. Today, a whole generation of Kurdish women have grown up taking a women’s army for granted, but at the time it was a tremendous step. The PKK movement could never have grown so large without someone having the foresight to think of ideas that might take a decade or more to develop and implement. Öcalan already said to us in the 1990s that ecology will be the decisive issue in Europe, also that we have to kill the Europeans, that is, the Eurocentrism, in us. He is always far ahead of his time, his analysis shows real solutions to the problems of humanity. Only later, when I read his books, could I begin to understand that.”

When Rêber Apo had to leave Syria and travel to Europe, what was that like for you?

“At first it was very exciting, it would have offered many opportunities to have a real discussion about how to solve the Kurdish question here in Europe. In retrospect, however, it became clear that the preparations and assessments of the friends who had prepared this were not sufficient, that they had bet on the wrong friends, had not seen that NATO would do everything to destroy Öcalan. That was then a very nerve-wracking time between hoping and fearing.”

When you learned that Rêber Apo had been captured in Kenya, how did you felt?

“I can say that was really one of the worst days in my life. I had associated so much hope for the emergence of a new internationalist, revolutionary movement with getting to know the Kurdish movement. On February 15, 1999, however, everything seemed to be in question. Abdullah Öcalan was presented in a degrading way in the Turkish media, the death penalty was pronounced and it seemed that this was the end of the PKK movement. Dozens of friends around the world publicly burned themselves, including people I knew. In Hamburg, comrades had occupied the SPD office, there were countless arrests, and in Berlin three young Kurds were shot in front of the Israeli embassy. Large parts of the left in Germany, including the Turkish left, did not show any solidarity, but spread defeatism. The Kurdish movement in Europe reacted partly headless, that was also what this NATO plot wanted to achieve, to take away the head of the movement. At the same time, the determined resistance, especially of the Kurdish youth, prevented the execution of Ocalan and that is a victory that was won in spite of everything. Many did not hesitate to express their anger and determination willfully. You couldn’t see it at the time, but in the end the movement has emerged stronger from this defeat, even if it took a few years to consolidate.”

Chairman Abdullah Öcalan has since been imprisoned and held under severe isolation torture in the maximum security prison on Imrali Island. There, he is putting up the greatest resistance in history. But the fascist regime of Turkey, despite the many protests and actions in Kurdistan and worldwide, makes no steps to release him. Now, since March 25, 2021, there is no contact with him and the other prisoners in Imrali. What message do you have for his release? What would you like to say about this in conclusion?

“In conclusion, I would like to say that we have to take off the European glasses to understand Ocalan’s message, to understand where we stand and where our enemy stands. The fact that Abdullah Öcalan is subjected to this isolation means that we should all be prevented from dealing with his proposals. He has shown us a way out of the deep crisis of capitalist patriarchy. We all see that we are ruining our Mother Earth. There is an urgent need for an alternative to this economic and social system that only brings destruction, suffering and misery – climate catastrophe, wars, epidemics, genocides, femicides. Öcalan has shown us an alternative with Democratic Confederalism, as it is being implemented in Rojava. More and more people in Afghanistan or Iran, among other places, are fighting for this alternative under the slogan “Jin Jiyan Azadî” coined by Abdullah Öcalan and the Kurdish women’s movement. It is not about superficial individual freedom, but about overturning the entire patriarchal system toward a grassroots, diverse, gender-free and ecological society. Öcalan, despite the extreme conditions on Imrali, has expended all his energy to counter a manual on how we can change the world. If we were really united, we would have the power to get him out of the dungeon. I don’t think there is any point in appealing to the ruling states and their non-existent humanism. Rather, as leftist, feminist forces, we need to rally society to increase the pressure on the states so that we can get the chairman released. This is also how we succeeded in freeing Nelson Mandela. As long as Abdullah Öcalan is behind bars, I don’t feel free either.”