BRAZIL – The indigenous peoples are painfully resisting a process of dismantling the institutions that should safeguard their rights, their territories, and the protection of their ways of being and living. And, more than anything, they are subjected to a dramatic context of systemic and institutionalized violence. Bodies, spirits, lands, and waters suffer cruel aggressions, and the lives of children, young people, men, women, and the elderly are being annihilated under the omission and silent connivance of public entities and agents.

The report with data from 2021, published by the Indigenous Missionary Council (Cimi), brings impacting numbers of cruelty, brutality, forcefulness, and continuity of invasions, fires, deforestation, subdivisions and permanent evictions, as well as aggression against indigenous lives, expressed in beatings, torture, poisoning, and murder.

Rape of girls, rape of boys, poisoned food and drink, attacks on villages, fires in prayer houses, and lacerated bodies – these topics of violence sound like the narratives of horror series and movie scripts, or recall the historical records of the periods when the Indians were hunted by settlers, bandeirantes, and slavers. And all, contumaciously, happened in 2021 and will continue in the data records for the year 2022.

This article – which is part of the introduction to the report – seeks to expose what the year 2021 meant for the indigenous peoples in Brazil, and it can be said, from the data and narratives presented in the report, that this year may have been, for many peoples, the worst of this century.

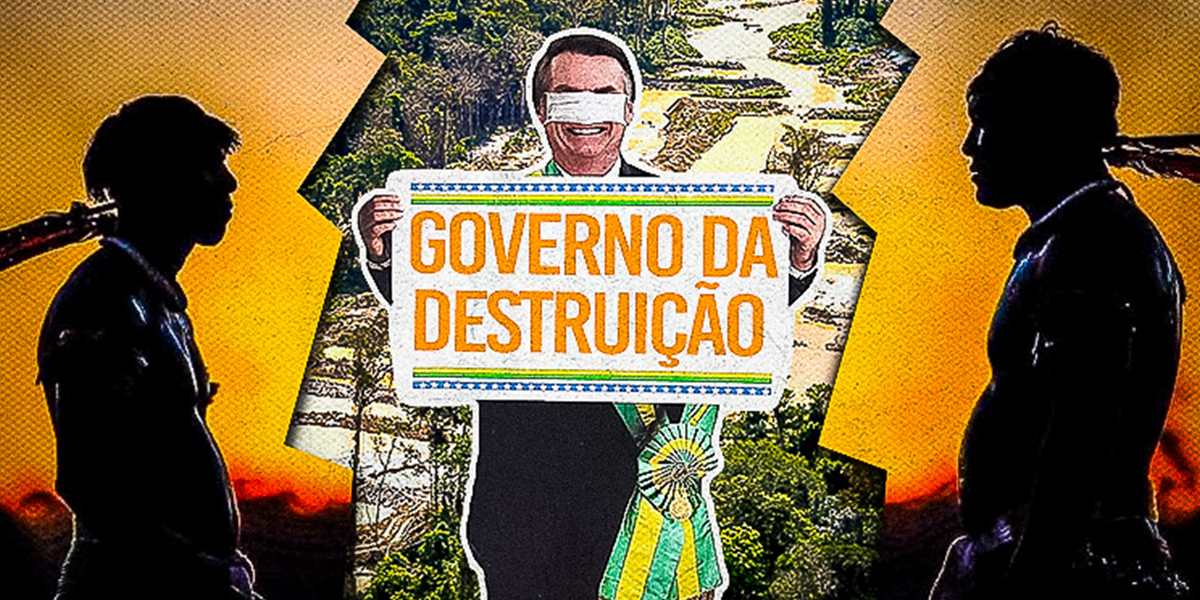

Under Bolsonaro’s government, at least two underlying conceptions have been introduced into the State’s relationship with indigenous peoples that underlie crimes and impunity: the first is linked to the idea that indigenous people are not subjects of rights like other humans, with the logic of the “savage” prevailing who, as such, can be assaulted, attacked, expelled or killed; the second is linked to the nefarious idea that the peoples do not need land and that everything done for them, in terms of public policies, is a privilege; therefore, ignoring them, integrating them, raping them and even killing them are not problems.

These conceptions were fed exhaustively by members of the government and projected through speeches that encouraged land invasions with the argument that “the Indians don’t produce,” or that “they are humanizing themselves,” or that lands would not be demarcated because there would be “too much land for too few Indians.

In this environment, Funai, the official indigenous body, has become a regulatory agency for criminal deals in the demarcated or demarcating territories. The Bolsonaro government has naturalized the violence practiced by invaders for the extraction of wood, minerals, and for the practice of mining, and has legalized the illegal occupation and subdivision of federal lands – after all, indigenous lands are federal property, as established by the Federal Constitution.

The invasions intensified because the inspection and protection agencies changed their objectives, becoming intermediaries and endorsers of criminal businesses on indigenous lands. And the civil servants who countered and sought to fulfill their functions were exonerated or – and there are cases – murdered. In other words, Bolsonaro excels in anti-politics, anti-law management. In Brazil, the thesis that crime pays is validated, as long as it is minimally organized, articulated, has a state interest, and is structured to exploit the land and its resources indiscriminately. And those men and women who oppose it tend to be repelled – often murder is the quickest way to get rid of the opponent.

INVASIONS AND DAMAGE OF THE INDIGENOUS LAND

In recent years, FUNAI, through ordinances, normative instructions, and decrees, has encouraged the illegal appropriation of indigenous lands for sale – subdivisions – and occupation by third parties, including timber harvesting, opening of pastures, monoculture plantations, gold mining, opening of roads, illegal squatting, and other illegal activities.

In the year 2021, we note that these criminal activities not only continued but also expanded in relation to previous years. This fact is expressed by the unprecedented number of cases of invasions of land, illegal exploitation of natural resources, and diverse damages to indigenous patrimony: 305 cases of this type were registered in 22 states of the federation, affecting 226 indigenous lands.

The Brazilian government has encouraged illegal invasions and pressured public agents to take a position in favor of exploiting indigenous lands, seeking to legalize them by means of legislative proposals such as Draft Laws (PLs) 191/2020, authored by the government itself, and 490/2007, approved by the Commission on Constitution, Justice, and Citizenship (CCJC) of the House of Representatives with strong support from the governing base.

The possessory invasions have taken on dramatic proportions this year due to their intensity, continuity, quantity, and the imposition of force and violence against communities within their own territories. Among the peoples most attacked by the criminal advance of the invaders are the Yanomami, in Roraima and Amazonas, Munduruku, in Pará, Pataxó, in Bahia, Mura, in Amazonas, Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and Karipuna, in Rondônia, Chiquitano in Mato Grosso, and Kadiwéu in Mato Grosso do Sul.

This situation of complete abandonment has led many peoples to create on their own territorial monitoring brigades, forest guardian groups, and lookout posts. In addition, several peoples have created sanitary barriers to control the entry of strangers into their living spaces in order to protect themselves from the pandemic. Many of these barriers were destroyed by invaders – and in some cases by the Military Police (PM), as occurred in the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Land (TI) in Roraima.

It is important to emphasize that it was verified that 28 ITs were invaded where there are 53 registrations of the presence of isolated peoples. This means that the majority of the 54 ITs with the presence of isolated peoples, according to the base of Cimi’s Support Team for Free Peoples (Eapil), were affected by cases of this type.

The conflicts related to territorial rights, in this report, present 118 occurrences in at least 20 states, aggravated by conflicts motivated by the leasing of indigenous lands, especially in Rio Grande do Sul and Mato Grosso, for the planting of transgenic soy, corn, and wheat seeds, in addition to the opening of pastures; many of these practices have been encouraged by Funai agents together with local ranchers and interested politicians.

Other measures by the federal government have also continued to foment conflicts and damage to indigenous patrimony, as in the case of FUNAI’s Normative Instruction 09/2020, which authorized the certification of private properties on unapproved indigenous lands. According to a survey by Agência Pública, in two years of effectiveness, this measure allowed for the certification of 239,000 hectares of farms within indigenous areas.

We have registered criminal actions, such as attacks with fires on prayer houses and Guarani and Kaiowá dwellings in Mato Grosso do Sul, and violent actions in movements for the subdivision of land in the states of Rondônia, Mato Grosso, Pará and Maranhão, even with the sale of lots carried out over the internet. This was the case of the real estate ads that sold lots inside the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau TI, verified by an investigation by BBC Brazil. The situation culminated in an action and decision by the STF to identify the criminals.

These numbers surpass those of 2020, when we had registered 96 cases of conflicts over land and 271 cases of invasion, illegal exploitation of natural resources, and various damages to property in at least 201 ITs.

READ ALSO: The destruction of the Environment worsened in Brazil since the election of Bolsonaro

Among the types of invasions and damage to indigenous patrimony registered in 2021, the extensive advance of mining in various indigenous lands stands out. There were at least 44 Indigenous Lands invaded by miners or affected by the environmental damage caused by mining and mining, such as water pollution with toxic substances like mercury and the destruction of entire rivers and streams.

This advance of miners, encouraged by the lack of enforcement, by the discourse and by practical actions of the federal government, such as PL 191, has also resulted in a worrying increase in direct violence against leaders and entire communities, which has especially severely affected the Munduruku people in Pará and the Yanomami people in Roraima and Amazonas.

The stunning devastation of these territories was accompanied by armed attacks against entire communities, death threats to leaders, the destruction of the headquarters of a Munduruku women’s association, and the criminal burning of the house of a leadership of the people opposed to mining.

In 2019, the Hutukara Associação Yanomami (HAY) already estimated the illegal presence of 20,000 miners in the Yanomami territory. The reports and the situations verified in the territory have worsened considerably, making an absurd scenario feasible: it is possible that today the amount of invaders installed in the Yanomami IT – under the indifferent eye of the State – equals the indigenous population of the territory, estimated by Sesai at 28,000 people.

One thousand hectares of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory were devastated by mining in 2021, and the total area destroyed in December reached an incredible 3,272 hectares, according to the monitoring of the Yanomami and Ye’kwana peoples carried out with the technical assistance of the Socio-environmental Institute (ISA).

This situation was reflected in a sequence of attacks on Yanomami communities over the course of months. HAY registered at least 16 of these attacks in letters sent to public authorities; the sequence of denunciations is a distressing record of the climate of terror and the passivity of the federal government.

The criminal destruction of several indigenous lands is also accompanied by a huge amount of mining applications overlaying these territories, covering up to 5.92 million hectares of these areas, according to the Amazônia Minada project, of the InfoAmazônia portal.

There are many complaints from indigenous people pointing out the omissions of the public authorities in fulfilling their duty to inspect and protect indigenous lands, which adds to the omission – planned and announced by the president of the Republic when he was still a postulant for the position – in demarcating indigenous lands. The Bolsonaro government completed its third year making good on its promise not to demarcate “one centimeter” of indigenous land, which motivated at least 24 public civil actions by the MPF demanding action from Funai and the Union.

The delay in the demarcations is long-standing, and the liabilities place several indigenous communities in situations of extreme vulnerability, fomenting conflicts and violations. Some communities have been waiting for action for decades. No indigenous land has been demarcated since 2016 and for three years now, not only has the demarcation process been completely paralyzed, but the government of Jair Bolsonaro has been infringing and seeking to alter the Federal Constitution in order to make indigenous territorial rights permanently unviable.

VIOLENCE, ABUSES AND OMISSIONS

The omissions of the federal government in relation to the protection of indigenous territories also affected other aspects of the lives of the native peoples, with emphasis on the various cases of lack of health care and the generalized lack of basic sanitation – especially serious situations in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The authoritarian character of the government was also expressed by the way it reacted to criticism and denunciations, which would be legitimate in any democratic environment, made by indigenous peoples and their organizations.

In a clear abuse of power, Funai even requested the Federal Police to open an inquiry to investigate the contents of the videos broadcast by the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib) in 2020. After that, in 2021, the national coordinator of the organization, Sônia Guajajara, was subpoenaed to testify in this investigation. Almir Suruí was also subpoenaed more than once to provide explanations to the Federal Police regarding the activities of two institutions coordinated by him. Pressure and intimidation were constant during the year.

The unprecedented increase in cases of “abuse of power”, in fact, indicates the reverberation, in the various regions of the country, of the mentality and authoritarianism expressed by the actions and omissions of the federal government. In 2021, 33 cases of this type were recorded, more than double the records in 2020 (14) and 2019 (13) and three times the amount recorded in 2018 (11). The case of the teacher and researcher Márcia Mura, dismissed from a public school in Porto Velho (RO) for “insisting on the indigenous theme,” was emblematic.

Throughout this period, the president of FUNAI was busy reformulating the staff, replacing civilians and career civil servants by military personnel, who by February 2021 already occupied almost 60% of the regional coordinations of the agency in the Legal Amazon. Captains, lieutenants, marines, among others, hold these positions in the Amazon; in the other regions of Brazil, military personnel account for 26.7% of the coordinators. Even with this contingent, not counting those who occupy secondary and service positions, FUNAI does not inspect, protect, or prevent the invasion of indigenous lands.

Based on data from the Mortality Information System (SIM) and state secretaries, we arrived at the number of 176 murders of indigenous people that occurred in the year 2021. This figure, slightly lower than the 182 murders registered in 2020, is still much higher than the murders of indigenous people registered in the previous five years (2015-2019), when the average was 123 indigenous people murdered per year.

Based on information from Cimi regional offices, indigenous leaders and news published by the press, our report registers and qualifies the occurrence of 77 cases, which allows us to take a closer look at the circumstances of these deaths. The murders of children are striking because of their form and cruelty. We highlight below some of these heinous crimes.

“We have seen day after day the murder of indigenous people. But, it seems that killing is not enough. The refinement of cruelty is what tears our soul apart, just as they literally tore apart the young body of Daiane, just 14 years old,” said the National Articulation of Women Warriors of Ancestry (Anmiga), in a statement. “The inhumanity displayed on indigenous female bodies needs to stop.”

LIVES LOST

The data recorded by the report indicate that the various omissions of the federal government, and the many conflicts and situations of vulnerability that result from them, have had serious reflections for the entire indigenous population of the country. The year 2021 was marked by a large number of indigenous lives lost.

The number of indigenous suicides was alarming this year, reaching 148 cases in 20 states, according to data from the SIM and state health departments. Of this total, 33 were female and 115 were male. The states with the most cases were Amazonas (51), Mato Grosso do Sul (35), and Roraima (13).

Equally alarming was the information registered by Cimi, Sesai, and SIM regarding infant mortality, deaths without assistance, and deaths due to Covid-19.

The data on infant mortality obtained from Sesai, with the cut-off of cases between 0 and 5 years of age, total 744 deaths. It is important to note that this number is certainly out of date, since the information provided by the secretariat to Cimi via the Access to Information Law (LAI) was collected in January 2022.

In 2021, Cimi recorded 39 deaths due to lack of health care – the highest number recorded since at least 2015. Sesai’s data, in turn, classifies 124 as “deaths without assistance.”

The serious consequences of the pandemic among indigenous peoples in Brazil are also evidenced by the SIM data, which registers 847 indigenous deaths due to coronavirus infection in 2021. Sesai registers, in the same period, 315 indigenous deaths from Covid-19.

This discrepancy is partly explained by the fact that Sesai only computes data referring to indigenous people treated by the Indigenous Health Care Subsystem (SasiSUS), which does not include, for example, indigenous people in urban contexts and many peoples and communities fighting for land.

Nevertheless, these data show the possible underreporting of indigenous deaths in the midst of the pandemic, widely denounced by indigenous organizations such as Apib, and sound a warning: these deaths occurred when vaccination had already begun, and seem to corroborate the accusations that a considerable part of the indigenous population was largely unattended in the midst of the health crisis.

Faced with this scenario of violence, administrative, legislative, and legal measures are necessary, but articulated together. And, among all the measures, it is imperative that the Federal Constitution be respected in its articles 231 and 232, where the rights and obligations of public agencies are also expressed. In any case, the demarcation of the lands, their inspection and protection; the structuring of public policies that respect ethnic and cultural differences and the peoples’ ways of being and living, and the administrative and judicial accountability of all those who committed crimes against life, against the environment, and against the public patrimony, are urgently needed.