“Summer in Rojava, 15 hours in the afternoon in the center of HPC-Jin (Hêzên Parastina Civak – Jin, Forces of Civil Defence) on the outskirts of a small town, where everyone knows each other. It’s hard to breathe at 47 degrees. It is a strong wind, very hot, that moves and lifts the dry land from the infinite wheat fields, already bare, that draw this flat landscape, with the mountains of Bakur in the background. Between us and the mountains, the border with the other Kurdistan, the one that some that mark the lines in the maps insist on calling Turkey.

I look out the window waiting for the women. I see in the cloud of dust the child on top of the donkey that walks the sheep here in front of us every day. Luckily he has his head covered, I think, although I have known other children who do not cover their heads, working or playing in the sun at any time. But most people wear it. It is characteristic of this place, whether you are Arab, Kurdish or Yezidi, whether you are an atheist, Christian or Muslim, whether you are an internationalist anarchist or a Kurdish revolutionary. It is something that equals all of us who walk in this area and you do not run the risk of cultural appropriation, because its usefulness is unquestionable. It is, at the same time, necessity and identity; although it is not by chance that in summer it takes more of the target. I myself, who had said before leaving my land, “I can manage with a cap”, have a kefiya that saves my ears from the flames. It is a treasure. It was given to me by the comrade of Kongra Star, with whom I spent some time in the surrounding villages, learning at her side, from her revolutionary work, admiring her and all that she represents, which is the struggle of women, of an entire people. It represents the fusion of all forms of self-defense, now materialized in work in society.

The one that gave me my second name in memory of a fallen comrade. One thought leads to another. I think of her, of the importance of her house-to-house work, which is the key to keeping the revolution alive, especially in these times of special warfare, when the efforts of the enemies are focused on wearing down society through economic drowning, water and electricity cuts, arson, and the introduction of drugs… All of this is aimed at demoralizing people so that they stop believing in this new community organization that has been built without a state, this example to the world. How important it is to keep morale high, to be with the people, to really believe. To do this, the tool of perwerde (formations)… The word brings me back to the present moment after entering into all these thoughts.

The women I wait for are late for training, as always, and I despair. My analytical, European, calculating mentality, which I insist on naming “realistic”, once again plays tricks on me: “If it would be as easy as the driver going out earlier to get them; if we know that the electricity goes out every day at five o’clock, why don’t we start a little earlier instead of dying of heat when the fans are turned off; how can this movement be so effective for some things and so little for others? And I get bad European blood… Then I go back to my learning at Rojava: it’s not about me; it’s about all of us.

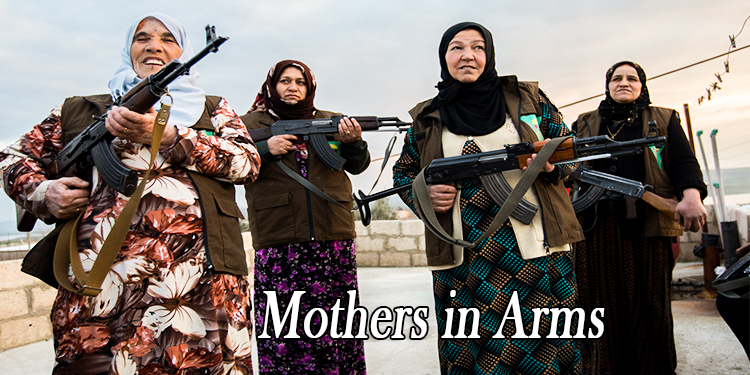

Finally, it’s 3 p.m. They are all members of HPC-Jin. They’re women in society, most of them mothers who work all day long, especially doing housework, with all that that implies. With an average of 7 to 10 daughters each, they carry the responsibility of cleaning, maintaining their whole family, eating or not eating, etc. They are tired, their knees, back and head hurt. In the time that they do not do this, they do everything that it implies for them to have joined the HPC: formations like this one, coordination assemblies, taking the defense of the demonstrations and the burials and ceremonies in memory of the şehîds (martyrs), presence and control on the roads in the campaigns against the fire, permanent availability in case of unforeseen events, neighborhood organization in moments of war, etc. The youngest must be about 20 years old and the oldest about 70, although it is impossible to know their ages, as they themselves do not know them. They are Kurds who have grown up without documents because they were not recognized by a Syrian state that forbade them to have their own identity (speak their language, wear their clothes, and celebrate their culture); besides, they do not usually celebrate birthdays, so of course, they do not keep track. Is it really so important to know the age?

They arrive saying “Yadeeee, germ e, germ e!” (mothereeee, it’s so hot!) and, automatically afterwards: “Where is the chay (tea)”, they ask me. They know that I am always the first one to arrive, and sometimes I have it ready for when they arrive. I tell them again that I have stopped preparing it because they don’t like the way I do it. Many internationalist comrades (eşnabî, as we are called here) use the big kettle with boiling water, and the small kettle with the concentrated chay and then mix it so that each one chooses her own proportions and whether she wants sugar or not. Here, in this part of Kurdistan, it is taken already mixed in a single teapot and with significant amounts of sugar. Why would they have to choose different ways of doing it if it is a kind of consensus? They say I don’t know how to do it. “Poor eşnabî, she doesn’t know”, and despite my inefficiency in preparing the tea, they include me, they talk to me, they don’t judge my appearance, they offer me tobacco, they make me feel as one from here. We ask each other: how are you, what is your situation? And we answer something like “God, well, thank you, and you? We answer and repeat the same words every time our gaze meets another, about 15 times because here it is done like this. So we wait to finish the chay, already an hour late, with the room full of smoke. With the same interest they talk about the cream they put on their face as the oil with which they clean the kalash (AK-47), and some of them boast that they always keep it very clean.

Finally we started the session. Today the theme is Welatparezî, one of the ideological pillars of the theory of women’s liberation. A teacher from the city is coming to give the session. After talking about the love of nature, land and society, and the crucial importance of women in defending them, she asks: why did you join the HPC? The answers fill the room with a kind of fresh air, which is not made up of just words. It is also full of emotion, pride and hope. Still with the last Serêkaniyê war in their memories, thoughts, bodies and looks, they respond one by one. They are those that didn’t leave when the war (2019) began. Those that stayed in case they had to defend their house, their street, their neighborhood, their city and country, while news of people arrived, many relatives or acquaintances, fallen, displaced, occupation in all its cruel forms. While many others fled. They speak proudly of their attitude. They have chosen it. Being a member is an unpaid job. The requirement is to want it. Some are relatives of şehîds, starting with the oldest, who lost a daughter killed in Afrin by the Turkish state in 2018. She was killed, like so many others, when she was defending that land of olive trees from the Turkish invasion. Her body has never been recovered. She, the mother, warrior, fighter, has been active since the beginning of the revolution, and is a member of the HPC since its inception. Her other daughter is one of the guards working at the center, and is currently guarding the entrance gate. She is protecting us.

The answers to the teacher’s question are varied, but all exciting: love for the land, respect for those who gave their lives for it, the desire to stay, to fight, and not to give up their roots… They don’t want to go to Germany, even though many have family there. They have united for the future of their daughters and sons, for their neighbors, for the Revolution. They want to help make the movement stronger, to support from the local level the comrades who are at the front, to get up after each fall, to build a life in comradeship and equality, they have been inspired by the need, the pride… and what moves everything: xwebawerî (believe in themselves). Belief is the key. Serêkaniyê, like Afrin, has “lost” and this is something that is said with an immense weight and a knot in the stomach, but they continue winning because they have not stopped believing and fighting. These are all their words.

The fresh air molecules, which are heavier, go down, and my negative thoughts from an hour ago go out the window with the hot air molecules that go up. This is where you put everything on the scale and the strength of these companions and friends begins to weigh you more than the delay, the chay with a lot of sugar at 47 degrees of room temperature, and the fact of knowing that in a while the fans are going to be turned off and we are going to begin to say all of them, each one in its language, “yadeeeeee”, (“ai mareeeee” in my case).

I begin to admire their lives, their strength, constancy, determination, dignity. I begin to feel that I am in a class with 16 teachers and one student, which it’s me. It is part of the idea of formation that the movement has here. Everyone can be a teacher and a student at the same time. My absolute truths, my logics, are in serious doubt. Then you feel the inevitable silence. The fans have been turned off. We begin to sweat, to give ourselves air with the handkerchiefs that many take off from their heads and others do not. Among women, everything changes. Everything. I think that autonomous spaces allow all kinds of expressions, postures… they are essential. Just as in the rest of the world, here women are not free either. But the revolution is moving slowly, and it’s easy to see how much has changed since the beginning. Luckily, in each organization, institution, commune, there are autonomous spaces to support this joint construction that is intended to be free of patriarchy.

And, despite the heat that I would define as hellish, the lesson continues. I was not wrong about “Yadeee”, which is now said in a low voice so as not to interrupt the speakers, but I was wrong about everything else. Neither the late hour nor the heat have prevented today’s session from being perfect. It’s not about me. It’s about all of us. One of the great lessons that every internationalist must learn at Rojava.

And, despite the heat that I would define as hellish, the lesson continues. I was not wrong about “Yadeee”, which is now said in a low voice so as not to interrupt the speakers, but I was wrong about everything else. Neither the late hour nor the heat have prevented today’s session from being perfect. It’s not about me. It’s about all of us. One of the great lessons that every internationalist must learn at Rojava.

The training is named after the last şehîd identified in this area. The last day will come when we will invite the mother of this fellow fallen in the mountains to remember the life of her daughter. Her eyes will be wet with sorrow and emotion when she sees the framed photo we will give her of her young daughter and she will be grateful at the same time. A few days later I will see her again in the cemetery at şehîds, with the photo above another woman’s grave şehîd because this time there is no body either. That’s what bombs have; sometimes they don’t leave anything physical, although it’s true that, as is shouted and repeated here permanently, martyrs don’t die. They are present everywhere; we carry their names, their images, their strength, their energy, their memory. They are inspiration and example. Respect.

I will greet them. I know her. I was at her house the day she was given the news, watching her scream, cry and fall to the ground in pain. She will take my hand and look at me with the same sad and loving face at the same time, she will invite me and my companion’s eşnabîs to her home… and who knows, maybe she will join HPC too. Such is this society that lives with death and pain: strong, tireless, welcoming, fighting to the end. This is how these women are. They are an example. There is only one impossible thing here. It is impossible not to fall in love with them and with this Revolution.”